| Artist Bio: |

From the WISCONSIN ALUMNUS.: THERE'S NOT ONE American who has ever become a

master craftsman in the ancient Japanese art of color

wood-block printing. But Major Vincent Hack, '36, Falls

Church, Va., has probably progressed as far toward this goal

as any of his countrymen -and in another eight years he

hopes to attain that high rank.

It was back in 1947 that Maj. Hack, a medical artist,

arrived in Tokyo. He immediately searched out a wood-

block artist, Hiroshi Yoshida. "Teach me," the major asked,

"to make wood-block color prints."

Yoshida referred Major Hack to a wood-block cutter, the

cutter referred him to a printer, the printer referred him

Major and Mrs. Hack look over some of his fine color printing.

36

to another printer. It was, the major realized, the old run-

around. He went back to Yoshida, and after a year of per-

severance, won an offer of help as a result of a favor

rendered.

He spent the next six months learning color analysis. A

Japanese wood-block artist analyzes the picture he wishes to

reproduce to decide the colors he needs. He plans one wood-

cut for each color. He may plan two woodcuts or 30, gain-

ing range and subtlety as he increases the number. Then

the proper design is painstakingly carved on each block-

each swirl of color is duplicated precisely in wood. Next,

a printer brushes the proper colors on the blocks and rubs

a specially-made paper against each block in turn, varying

intensity of the colors by varying his pressure. Some author-

ities call the Japanese wood-block art the world's highest

developed color printing.

After Maj. Hack learned color analysis, he still had a

long way to go. He located a master cutter, and by dint

of more lengthy persuasion, extracted from him a promise:

"You will be a No. 1 American cutter."

The master cutter required Maj. Hack to hold an egg

against the handle of the cutting knife. If the egg broke,

it proved he was not using a delicate touch. For economy,

the cutter furnished only rotten eggs. After breaking a few,

Maj. Hack brought his own, fresh ones.

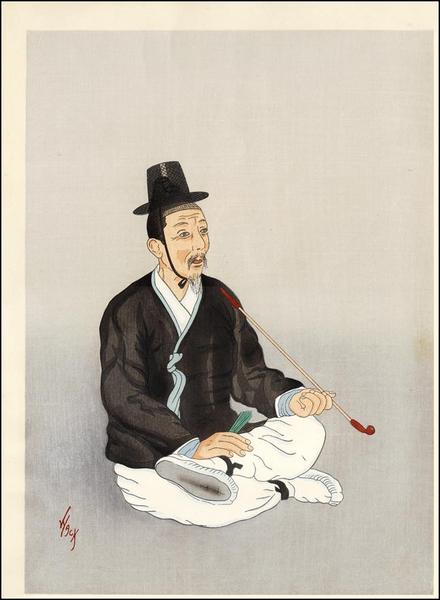

Before leaving Japan in 1951, Maj. Hack saw his prints

hanging in Japanese exhibitions. Some Japanese viewers

thought they were seeing a new school of wood-block print-

ing. Maj. Hack explains that he gives the faces of his sub-

jects more characterization than the Japanese do.

Maj. Hack is now with the Armed Forces Institute of

Pathology in Washington. He spends many off-duty hours

with his cherry-wood blocks. It requires about eight months

from conception of a painting to completion of prints.

|

|